The day-to-day work of providing government services involves collecting, using, and storing large amounts of data. The data that government agencies accumulate is a critical asset — it holds answers about which programs perform best, which interventions are most effective, and how to improve service delivery. Data can also be a liability when it falls into the wrong hands or is misused, even unintentionally. Data governance is a great place to start gaining control of your data.

Establishing data governance can be intimidating. Between resource constraints, multiple and different data policies within large organizations, cultural reluctance to change, and lack of knowledge, it can be difficult to even know where to begin. Start with the fundamentals: understand what data governance is, and why it is so important.

These initial guidelines will help you validate the need for data governance at your organization, and recognize the correlation between reaching your strategic goals and governing data.

So, what is it?

Data governance is an ongoing, evolutionary process driven by business leaders where they establish principles, policies, business rules, and metrics for data sharing. They manage priorities and resources such as data stewards and technologists to acquire, harmonize, summarize, and produce data-rich analyses of data assets required to meet agency goals.

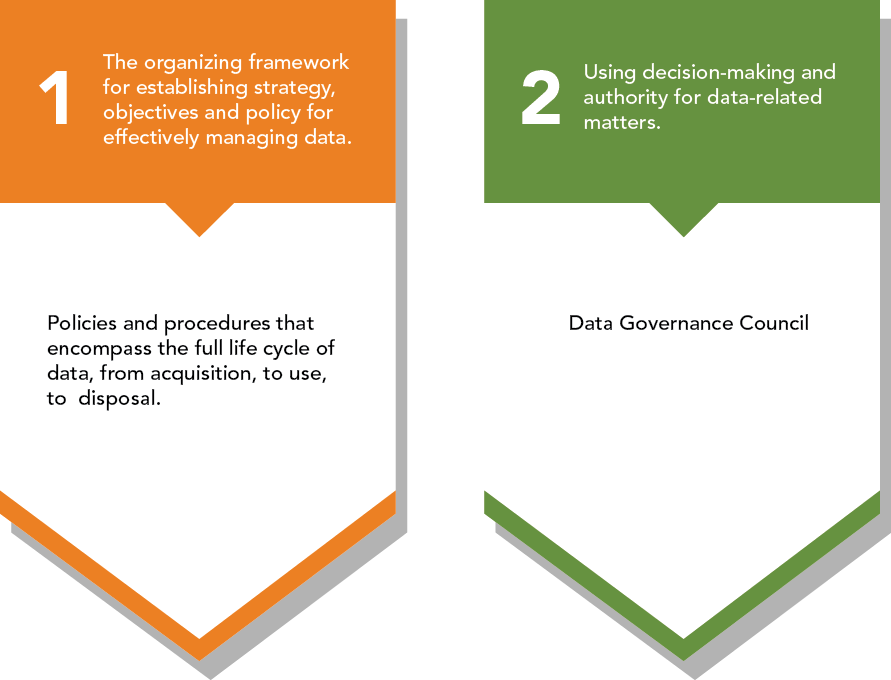

At a high-level, data governance has two main components:

Why is data governance so important, and why NOW?

- Data ownership is a responsibility. Properly governing data is not only important for organizational strategy, it is also important to produce high-quality client outcomes and levels of satisfaction. When you establish proper data policies and procedures, clients receive a better level of service.

- The amount of data collected is increasing. Many organizations collect an abundance of data, with no real vision of how to use it. A framework of data governance assists with developing a strategy to take advantage of data and use it effectively.

- The demand for data is growing. Organizations, especially in the public sector, are required to analyze and submit data for reporting to funders and oversight bodies. Without data governance, these reports can be inaccurate, contain gaps, or be manipulated improperly to produce false reports.

- The concern for security surrounding data is increasing. Mandates across both public and private sectors constantly evolve, because the more technical our world becomes, the more secure our data needs to be. If an organization does not implement foundational data security measures across all jurisdictions, it can become easy to fall behind the curve, and out of compliance.

- Organizations miss many opportunities to leverage data more efficiently. Organizations report being unable to provide a high level of confidence to produce accurate data reports, resulting in inefficient resource distribution. A standardized framework for governing data helps produce higher levels of data quality and integrity, and improves report accuracy.

How can your organization start the process?

The first step in a data governance initiative is to assess your organization’s data environment and maturity level. Start by analyzing your organization’s data policies, usage, documentation, and management processes to gain a true understanding of the current data landscape and management maturity level. CMMI’s Data Management Maturity Model (DMMM) and the Data Management Association’s Data Management Body of Knowledge (DMBOK) are great reference resources to assist with understanding the role and definition of data governance.

The time for data governance is now.

BerryDunn’s Government Consulting Group works with state agencies to develop data governance initiatives as well as specific processes and policies to help states take control of data, increase confidence in its quality, and reach strategic goals.